Jan 22, 2026

Arnon Shimoni

What Snowflake gets right, where Lovable breaks down, and why most teams end up in a maze of custom engineering.

Credits are everywhere now. Snowflake charges them for compute. OpenAI and Anthropic use prepaid balances. Black Forest Labs prices images at 2.5 credits each. Every AI product seems to have some version of "buy credits, burn credits".

But underneath the surface, these systems are architected very differently. Some are elegant. Some are brittle. And the difference determines whether your pricing can evolve with your product, or whether every change requires an engineering sprint.

I've spotted 3 patterns that seem to actually work (even if I'm not a fan of them):

How credits actually work in the wild

Pattern 1: Snowflake's universal abstraction

This one is strategically risky, but definitely influential. It's genuinely clever, albeit unfriendly to figure out.

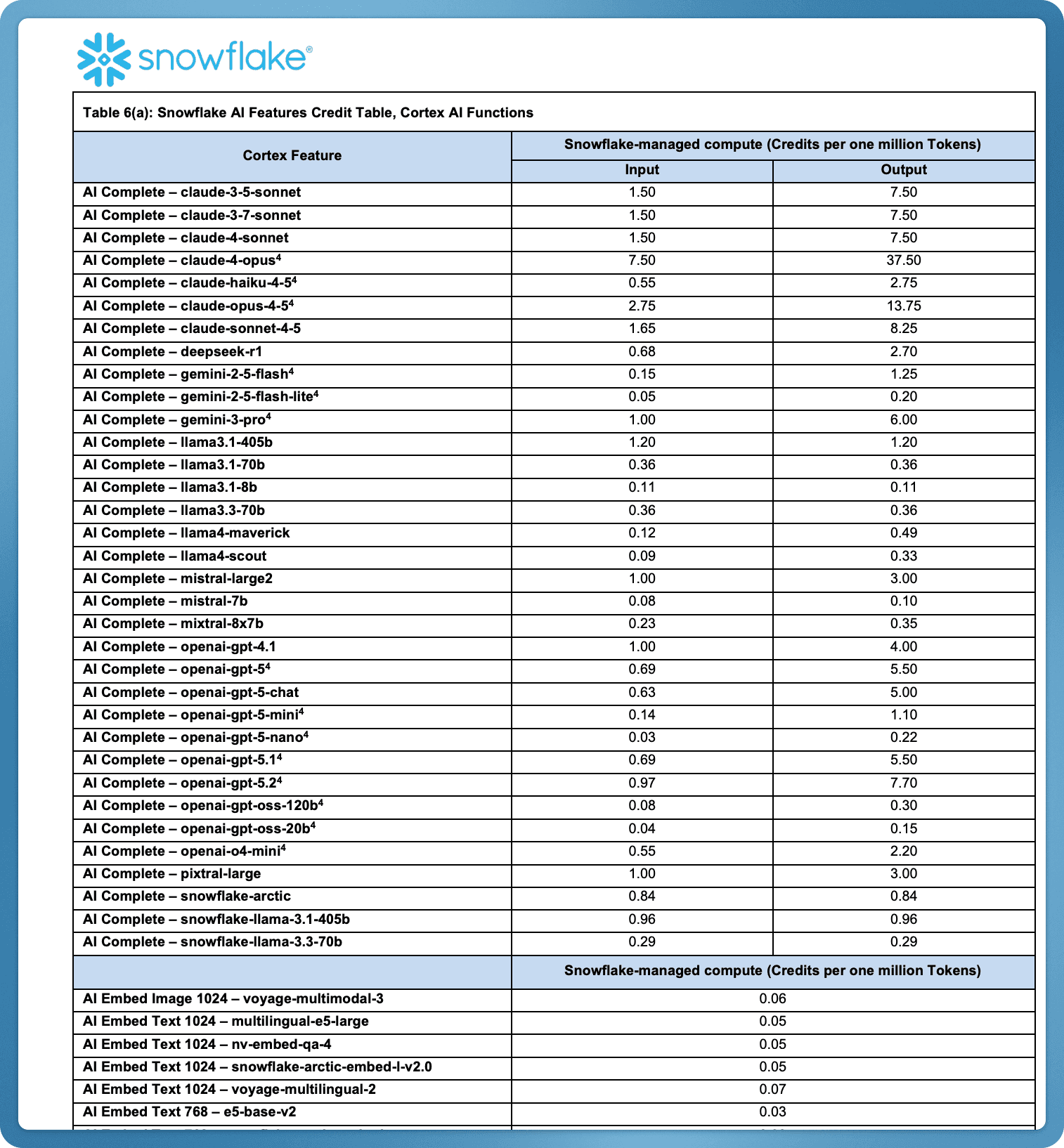

One "credit" abstracts over everything: warehouse compute, serverless features, AI/LLM calls. Internally, each resource maps to a conversion rate (e.g., "Model v1 = 1.7 credits per 1M tokens", and as models change - these credits per 1M tokens keeps changing, growing, and shrinking too).

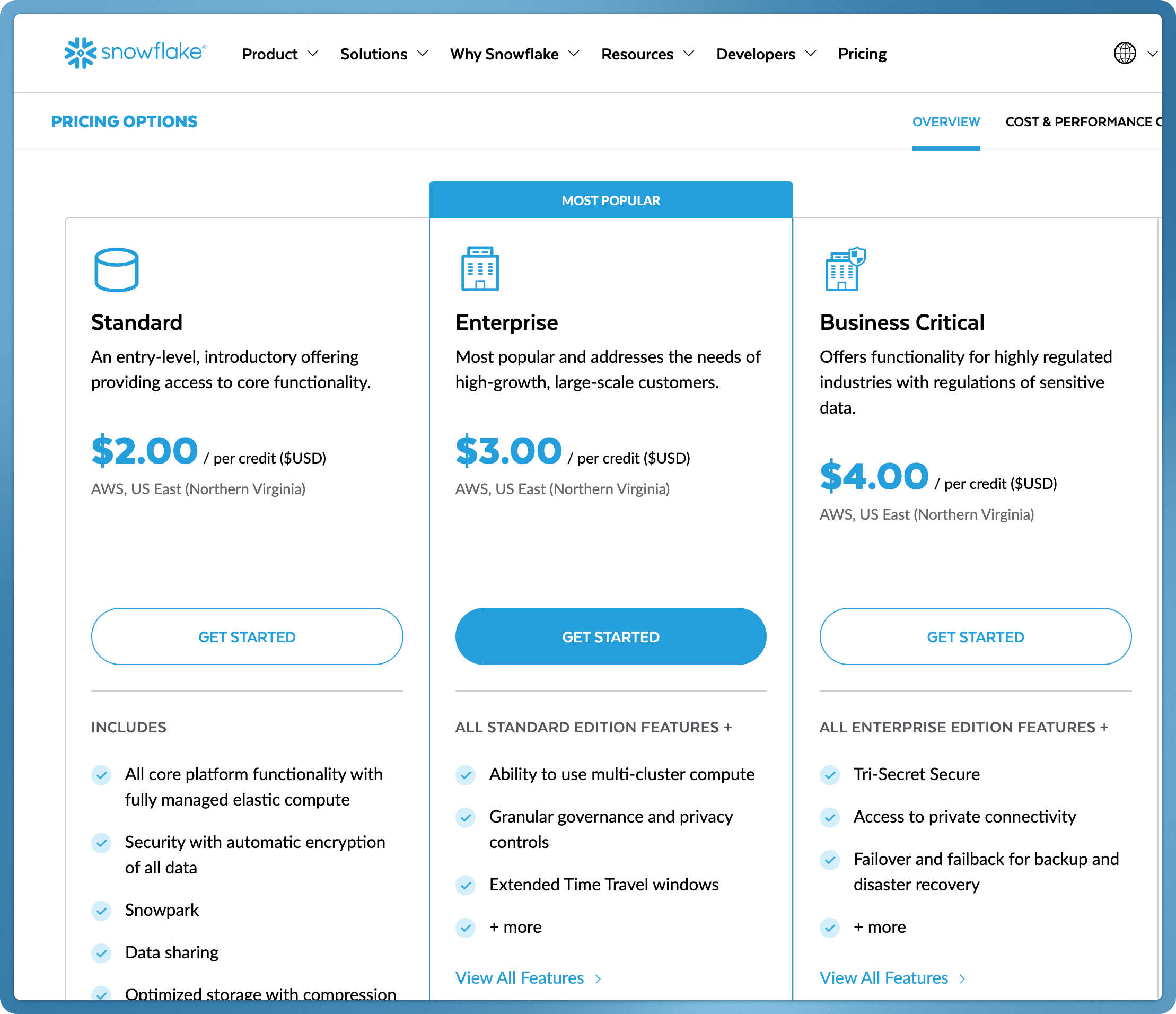

Externally, the customer sees a stable contract: "$3 per credit".

The power move for Snowflake is that when models or resources change, they adjust conversion rates in one place. They don't need customer approvals or renegotiation and no one notices because the visible price doesn't change.

For customers, this creates a trust problem, because it's really hard to figure out. You have to build a shadow model to reverse-engineer true costs. As usage scales, the abstraction becomes a complication. It obviously optimizes for their own vendor flexibility, not yours as a customer.

The tradeoff: customers can't easily figure out the costs while Snowflake can effectively raise prices by changing the credit-to-usage mappings without touching the headline $/credit as above.

It's an abstraction layer that benefits the vendor more than the buyer.

Pattern 2: OpenAI's wallet

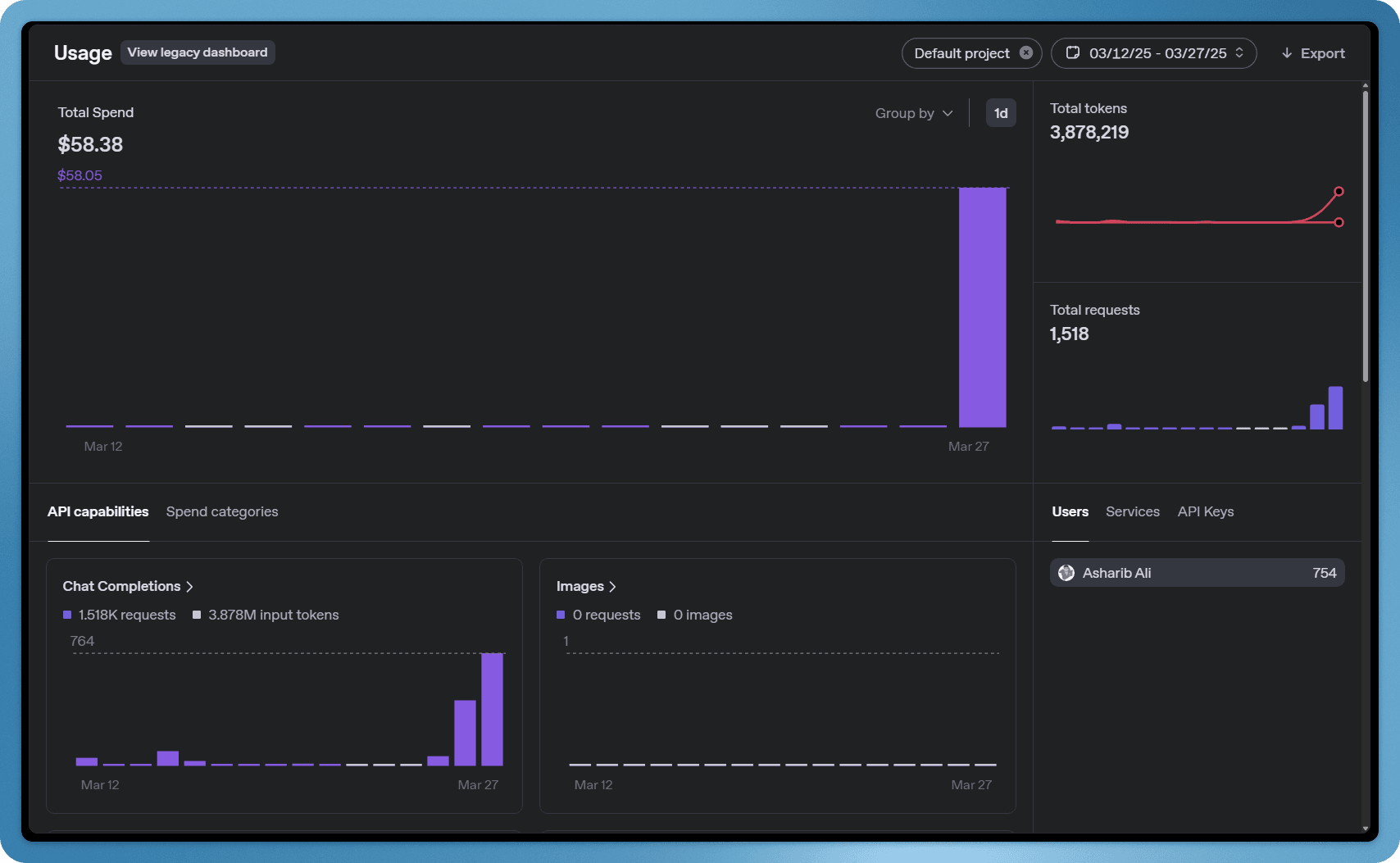

OpenAI (and Anthropic too) skip the "credit" abstraction.

You load money into a balance. Pricing is expressed directly as dollars per million tokens or similar. You configure org-level spend limits and draw down until you hit them.

This is more transparent, as there is no translation layer between usage and money but it's also rigid.

There's no clean way to handle multiple resource types (images, video, tokens) with different economics and org/team hierarchy controls are fragmented across multiple admin screens.

To be fair, this model exists for a reason. Wallets are the fastest way to give a hard spend limits in a volatile environment which they both operate in.

When demand is unpredictable, safety constraints are evolving, and usage can spike overnight, simplicity beats elegance. In early or chaotic phases, wallets aren’t a compromise but the right answer.

Pattern 3: Credits + slightly painful UX (Lovable)

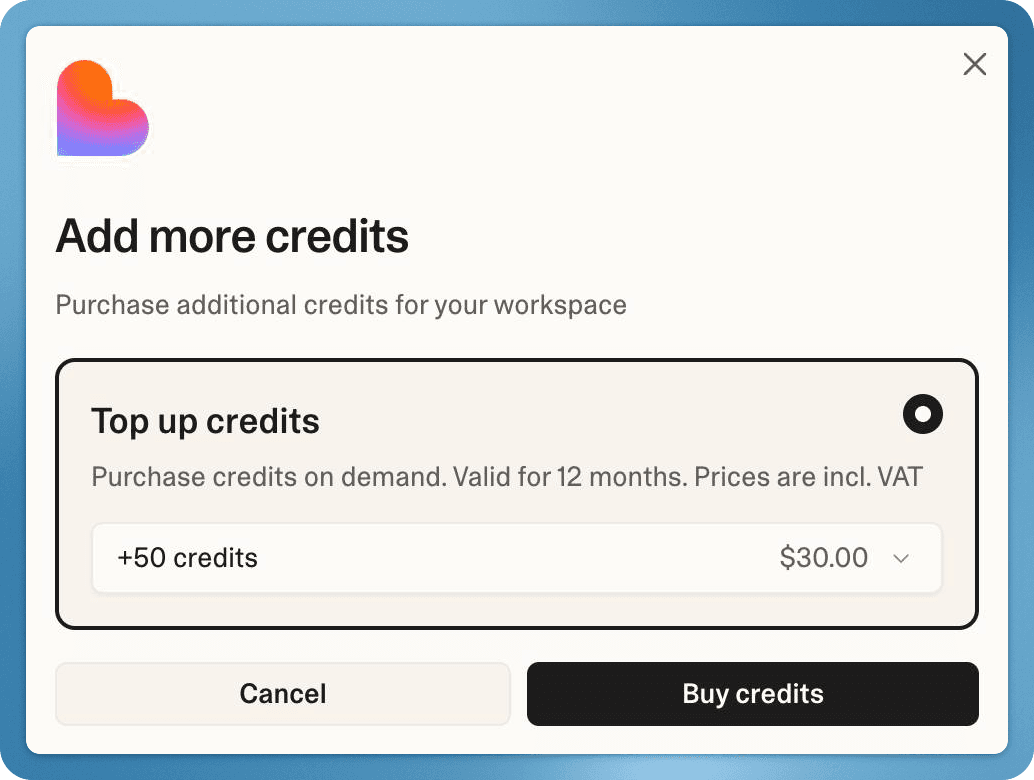

Lovable uses credits, but the implementation exposes the seams.

Granted, this is a new feature as of January 2026, but top-ups kick you into an external checkout flow. When a teammate hits their limit, the admin must manually navigate a separate payment process. No team-level budgets and auto top-ups. The credit model exists, but it's not integrated into how the organization works.

This is what happens when credits are bolted onto a billing system rather than treated as a ledger design decision.

The mechanics exist, but the organization model doesn’t really.

Moving from v1 to v2

Most teams building AI products end up somewhere between these patterns.

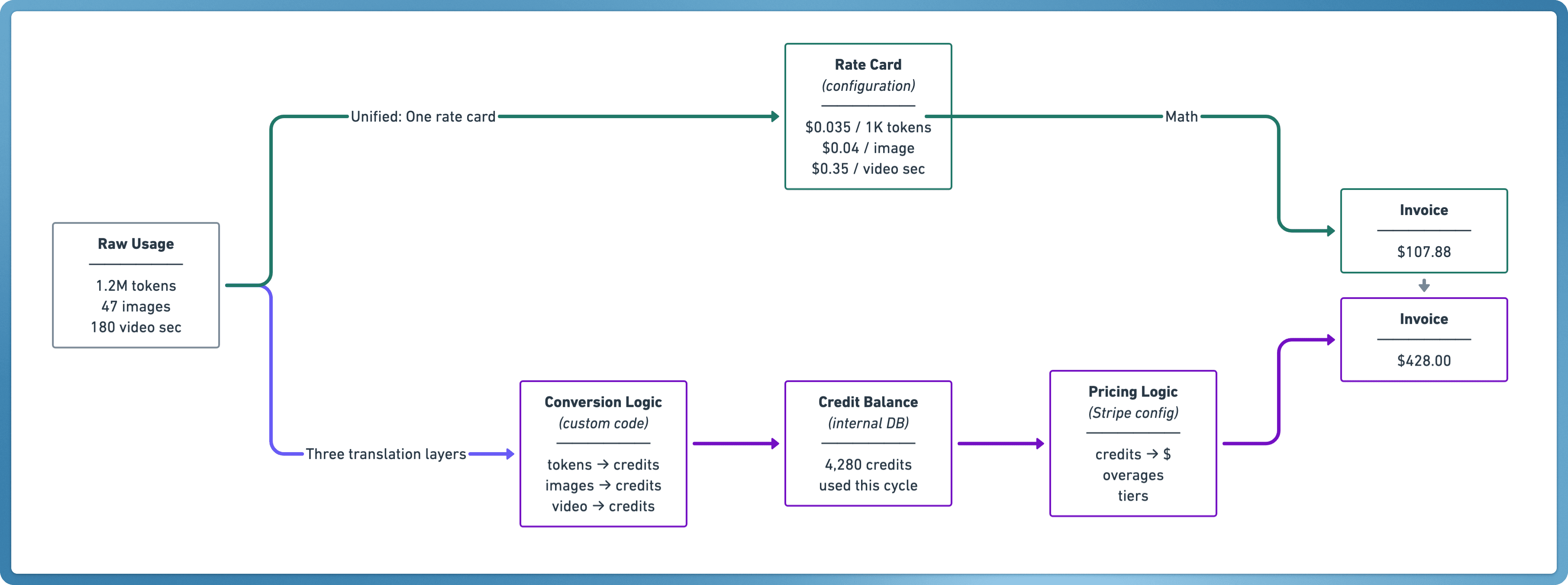

It's perfectly fine to start with Stripe for subscriptions, and then adding:

Custom code to convert raw usage (tokens, images, seconds) into credits or dollar charges

Internal logic for balances, wallets, rollovers, expiry

Separate admin tools for team budgets and approvals

A Stripe checkout that treats existing customers like first-time buyers

The result is fragmented pricing logic, partly in product code, partly in billing configuration, partly in finance spreadsheets (Spreadsheet in the Middle is a real problem).

When you build this way, changing pricing means engineers update conversion logic, finance updates the billing platform, and everyone hopes nothing breaks.

We also call this the "deploy code, not configuration" trap which we believe is dangerous. It sounds disciplined until finance and non-engineers realise they can't adjust pricing without waiting on engineering for every change. Every new model or feature requires new usage metrics, new credit mappings, and updates to multiple systems.

And then there's accounting. Credits are liabilities until consumed or expired. Companies often ignore proper revenue recognition early on, building ad-hoc balance logic that doesn't map to ASC 606 or IFRS 15. This becomes painful at scale especially during due diligence, M&A, or IPO preparation, when auditors start asking questions the system can't answer.

So what should things look like?

Here's what we believe at Solvimon:

1. Wallets and credits as distinct, composable primitives

A customer should be able to hold multiple wallet types:

a money wallet (prepaid balance in real currency)

separate credit wallets for different resource types, for example:

image credits

video credits

token credits

The billing system draws down from the correct wallet automatically based on what's consumed, with fallbacks if necessary.

This gives you the power of Snowflake's universal abstraction, but configurable rather than hardcoded.

You decide which resources consume which credits. You can mix prepaid credits with postpaid charges.

The data model supports it natively.

2. Configuration-driven pricing, not code-driven

Raw usage metrics (tokens, images, video seconds) should flow into the system separately from how they're priced.

The mapping between usage and money happens in a rate card is a configuration, not application code.

This means:

Finance can change the $/credit or credits-per-unit without a re-deploy

New models get added by defining their usage metrics and mapping them to existing wallets

Pricing iteration happens at product speed, not engineering speed

Snowflake's "single rate card" power, but under your control rather than locked inside a black box.

3. Org-level pools with guardrails

Credits should default to the organization level, not per-user islands.

Heavy users shouldn't drain the entire pool, so you layer on per-user or per-team limits as guardrails. But the pool is shared.

This avoids the "stranded assets" problem where companies pay for large allocations of credits but can't use them because credits are locked to individual users. In those cases, some power users hit limits while casual users sit on unused balances. It's artificial breakage that benefits vendors but erodes trust.

The correct model is org-level pools with user-level guardrails, and the flexibility to add team-level allowances as the org structure demands.

Are you ready for billing v2?

Honestly, none of this matters if you're pre-product-market-fit with simple subscription pricing. Stripe is fine. Lago is fine (and open source!). It'll hold, no problem.

But there's a point, usually around the time you're adding AI features, launching a second pricing model, or moving upmarket to enterprise contracts where the architecture starts to bind and hurt. Your pricing changes slow down.

When finance depends on engineering and top-up flows feel broken, and your auditors ask questions you can't answer.

That's the moment when "credits as a feature" reveals itself as "credits as a liability." Not the accounting kind. The architectural kind.

I find that credits are hard because most systems weren't designed for them from the start - not because the math is hard.